The Leaving Of Liverpool

- Paul Diggory

- May 24, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2021

At 11a.m. on 3rd September 1939, Mary Nolan shushed the kids and turned up the radio. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was about to broadcast an announcement.

“This nation is at war with Germany… I know that you will all play your part with calmness and courage”.

Children prepare to board trains for the leaving of Liverpool

Mary, my Nana, would need more than calmness and courage over the coming years. She’d have to bring up a new-born baby and three children under five in the most challenging circumstances. Less than three months earlier her husband, Peter Nolan, the Grandad I never met, walked out on his young family. His son Peter was five, Doreen four and Joan not yet two. Mary was seven months pregnant and had shown a lack of enthusiasm of late for going out at night, she'd rather stay in with her kids. Meanwhile, he’d been seeing another woman. My mother, Doreen, believed that her mother was happy that she had her children and was prepared to turn a blind eye as long as he came home. Finding out on the grapevine that the other woman was also pregnant pushed her too far and she confronted him.

Following a huge argument in the kitchen, despite her condition, he completely lost it and beat her badly, even ripping the dress off her back. Young Peter threw forks at him and shouted.

"Don't you hit my Mummy".

Doreen watched in horror from under the table, too afraid to do or say anything. Before storming out, her dad took off his belt and leathered them. The man who was an amateur boxer who fought many times at the legendary Liverpool Stadium and the recipient of an award for bravery from Liverpool Corporation left two children screaming and hysterical, his wife beaten and distraught.

Mary gave birth to her fourth child, Joyce, in August, a month after her husband’s new woman had given birth to hers. Doreen would see her dad just once more, very briefly, when she was 16.

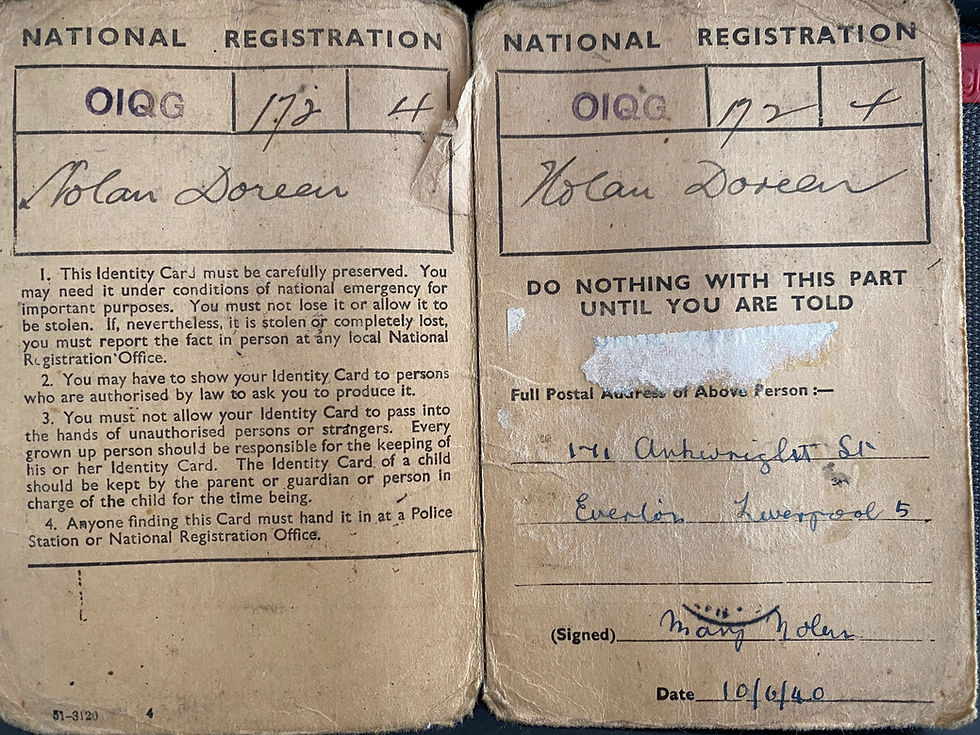

It was almost a year before Liverpool experienced its first air raid, in August 1940. The city was targeted regularly through that autumn with 15 raids in September and nine in October. As the main port for the Atlantic route to the USA, Liverpool was a key strategic target for the Luftwaffe. People had to carry identity cards - Doreen's was dated 10th June 1940 and showed her address as 171 Arkwright Street, Everton. There were blackout restrictions and they didn’t only cover the home. Street lighting and illuminated signs were extinguished and all vehicles had to put caps over their lights to dim them. In the early days of the war, people were forbidden even to carry torches. Inevitably the blackout caused a steady increase in accidents. According to a survey from January 1940, since the previous September, one in five people had been injured in the blackout. In the early days of the raids, the only casualty experienced by the Nolans was their cat. After several escapes, it finally used up its nine lives.

Sometime that autumn, the family were evacuated - to Whitchurch in North Shropshire. Thousands of children and families left the city in 1940, most headed for the relative safety of Lancashire, Cheshire, Shropshire and North Wales. Peter went alone initially so he could start school in September. He was billeted immediately to Wrexham Road with Mrs Wisdom, later moving again to live with Mr and Mrs Carter from Waymills. When the family followed on, Doreen recalled how strange it was, disembarking from the train in a strange town, not knowing where you’d be living. Whilst they received kindness from some, they also encountered hostility and prejudice from others. They were found accommodation together at Goodwin’s Farm at Grindley Brook, just outside the town. They’d never seen cows before and loved having the cream off the top of the milk every morning. Yet Mary, who’d shown such courage and resilience so far, was frightened of the cows and found it a struggle.

Back on Merseyside, the first major raid came on 28th/29th November when the city was hit by 350 tons of high explosive bombs and 3,000 incendiaries. Thirty land mines were dropped by parachute - what a terrifying and eery sight as they fell silently through the searchlights. Nearly 300 people were killed that night.

From 20th to 23rd December, the enemy launched a sustained attack for three consecutive nights. The docks were targeted on the first night with £4 million worth of timber destroyed as fires raged. After the Tate and Lyle factory was hit, people reported the sweetness of burned caramel hanging in the air around the city. There was also damage to the headquarters of the Cunard shipping line and the prestigious Adelphi Hotel. The second night saw the docks come under further bombardment. Residential areas in Bootle were also hit significantly. The glorious St George’s Hall was hit by incendiary bombs but the building was saved from serious damage by firefighters and civil defence workers. The following night the bombers returned. While the city's docks were again the main target, the surrounding streets of terraced houses were also badly hit, devastating the homes of dock workers and their families. The jangling bells of fire engines could be heard throughout the night. As people took stock on the morning of Christmas Eve, few could have expected Santa Claus to risk a visit that night.

In Whitchurch, as the Nolans stayed safe from the frightening devastation inflicted on their home city, raids on Liverpool slowed over the early months of 1941. This may have encouraged Mary’s decision to move her family back to the city. After seven months she remained unsettled. Their return, however, to their old home in Arkwright Street, was not well-timed.

Doreen came to dread the sound of sirens at night, forcing them to take refuge in the nearest shelter that had space. How tough must it have been for Mary on her own with three children, leaving her only son forty miles away in Whitchurch? Over the next few months her character and resilience would be severely tested. One night during an air raid the shelter warden, Mr Aspinall, gave her a cigarette and she smoked for the first time. Mr Aspinall said it would help to calm her nerves. After that, she always carried a packet of five Woodbines just in case.

The ‘May Blitz’ on Liverpool, from 1st to 7th May 1941, was the most concentrated series of air attacks on any British city region outside London during the Second World War. 681 planes dropped 870 tonnes of high explosives and more than 112,000 firebombs on Liverpool. German bombers typically dropped a combination of high explosive and incendiary bombs. Incendiaries would quickly start fierce fires unless they were extinguished immediately. To combat incendiaries, people were encouraged to volunteer as fire watchers and to draw up rotas with their neighbours.

The Nolan's home in Arkwright Street, Everton was destroyed after a German air raid

One night the Nolans returned from an air raid only to discover their home had been reduced to rubble. They found accommodation nearby at Howe Street in Everton, only for this house to suffer the same fate. Given the address of a shelter, they had to be turned away on arrival as little Joan had chicken pox. In urgent need of a roof over their heads before the raids began at night, they took refuge in a derelict house. Doreen remembered the big pillars outside and her mother taking them down some steps to the cellar, likely to be the safest part of the house. Mary sat on a chair in the corner with baby Joyce on her knee, while Doreen and Joan sat round her on the floor. They sang songs together to keep their spirits up.

“During the air raid” Doreen recalled, “there was a deafening explosion and everything caved in - you could see the stars”.

Despite that, they remained safe and emerged next morning to find loss and carnage all around.

“I remember" Doreen said, "there was a huge crater in the middle of the road outside the house.”

Then, in a chilling twist of fate, they discovered the building where they’d been turned away the previous afternoon had taken a direct hit. Everyone inside had been killed. Aunty Mary lived in Everton and let them move in with her family, where they slept on camp beds that could be folded and hung on the wall during the day to save space.

Doreen remembered living in the 'Scotch Houses' in Howe Street

Shortly after the ‘May Blitz’, the city received a visit from Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

"I see the damage done by the enemy attacks, but I also see...

the spirit of an unconquered people."

Later that summer, when Doreen was six, they returned to Whitchurch. They had to walk round town knocking on doors asking for people to take them in. The first person to help was Nurse Oliver, before they found room with Mrs Healey and her daughter Dolly. Desperate they may have been, but Doreen's memories of her time there were not positive. Luckily, Mrs Duckers soon let them move into 39 Green End, opposite the Fox and Goose pub, when at last Peter was able to rejoin his family. To help make ends meet, Mary took in laundry from American soldiers - there was a troop of US Forces stationed at Broughall School and an airfield at Prees Heath. It was at this address they were sometimes visited by her Uncle Leslie and Aunty Lily from Liverpool.

Two years later they moved to a house in Sherrymill Hill, shared with two Cockney women evacuated from London. Their colourful nature sometimes attracted American soldiers, who'd turn up at all times of the night, shouting and knocking on the windows to attract their attention. One of them became pregnant. Tragically the baby didn’t survive, the likely consequence of its mother’s lifestyle and the disease she carried throughout pregnancy. Eventually, they returned to London.

At the end of the war, Whitchurch held a big street party on VE Day which Doreen remembered warmly.

"Everybody was singing and dancing in the streets" she said. “It was like a Liverpool wedding. Only it didn’t go on as long."

Comments